12 minutes reading time

(2361 words)

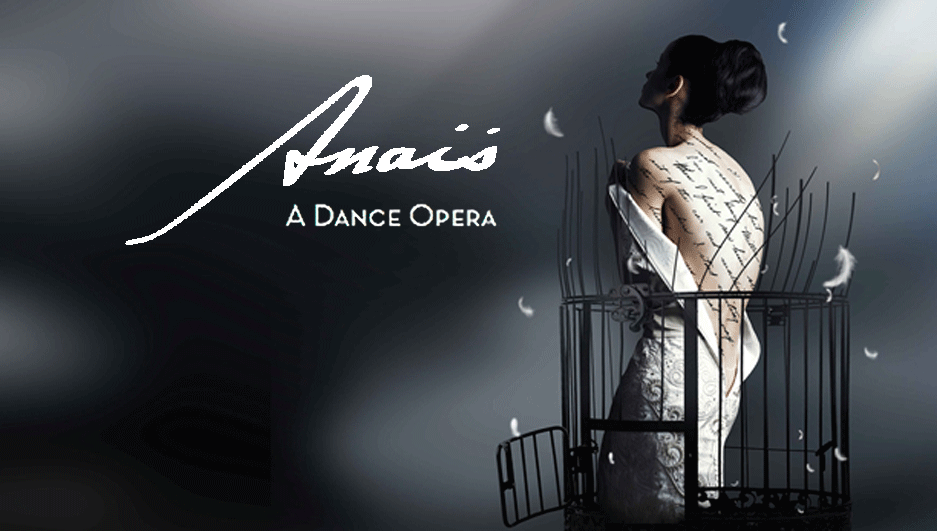

Dance: Anaїs by Mixed eMotion Theatrix

Dance

Anaїs by Mixed eMotion Theatrix

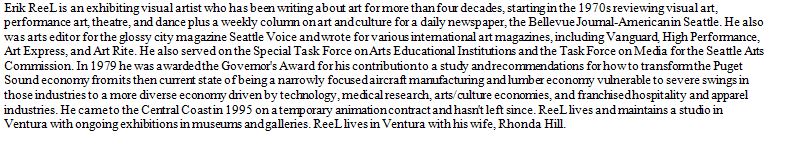

9 September 2017 -- The greatest strengths of Anaїs, a Dance Opera, other than the conception and timing of doing this work at this time to begin with, is, first, the work of both the lead dancer, Kate Coleman, and the voice, Holly Sedillos, at its center. Second, the choice of doing it with a minimal set backed by a projection scrim and using live and recorded sound, in short, a multi-media piece.

Photo Credit: Barry Weiss

Above all, this is a tribute to Anaїs Nin. It is a piece that does justice to Anaїs Nin, someone who is easily misunderstood, even by her biographers, and gives us an appropriately balanced, honest, and intriguing glimpse into her life and work and most importantly, why she might be important.

It is a credit to its creators’ insight to do a tribute to Anaїs Nin at this time. There are many and good reasons Nin will most likely be read and known well into the future. Some of which are peculiarly appropriate to today.

Another strength of the piece is the music by Cindy Shapiro. With a single voice carrying the entire sound track, one might think the music might start to sound to monotonous, as it often does in reviews of a single composer or lyricist. But not here. The score covers and carries the story, but remains musically interesting throughout. A lot of people coming out of the theatre were talking about the music, how much the music worked for them.

As for Anaїs Nin, the subject of this tribute, in her own time, between the two wars, Nin was fabulously famous. There was much envy and bewilderment amongst her peers. Oddly, Nin frequently complained through all her life that she was not appreciated enough or famous enough. In her mind, she didn’t get enough credit for her sexual politics and use of formal men’s wear and dozens of other things. In reality, her peers were more of the opposite opinion. Djuna Barnes wondered out loud how someone “who couldn’t even bother herself to write a decent novel” could become so famous as a writer. And there were plenty of women of Nin’s milieu, Djuna among them, who were at least if not more, radical in their use of men’s clothes and feminist sexual politics.

For example, Nin complained that Henry Miller got more respect and fame because he was a man. No, his fame and respect was based on the fact that he had written half a dozen masterpieces --almost as much prose as Proust and considerably more outrageous, while Nin had, at that point, only published part of an autobiography, where the parts left out were often the best, and juiciest parts, as the world found out half a century later.

Nin complained that she was inadequately appreciated as a literary stylist. But her language is almost maddingly pervaded by a certain vagueness, an unwillingness to dive into the guts of language, a refusal to use concrete nouns and hard adjectives. It was frequently contrasted against Miller’s.

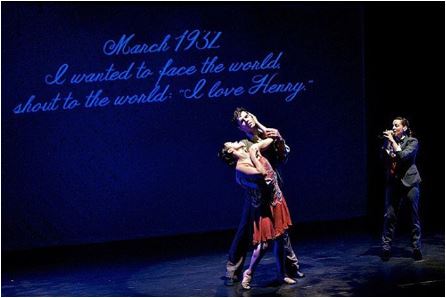

Photo Credit: Barry Weiss

To get a sense of how much of a contrast this is, Nin, when referring to a woman’s sexual parts used the old and conservative French custom of saying “a woman’s sex” while Miller, on the other hand, used just about every Anglo-Saxon term known plus a good dozen of his own original coinage in a prose strewn with graphic adjectives and nouns and hard-hitting, rambling, magnificent sentences.

On top of that, ironically, Nin was writing erotica, on commission. When it was published, it was seen to be quite tame, especially in comparison to the Parisian tradition that already existed, seeming oddly quaint, even naive. Nin’s erotica is too soft to even be considered soft-core, and she was consciously and explicitly writing erotica. Miller’s writing, on the other hand, which he never considered to be erotica, was filled with far more outright sex, was far more explicit, and consummately contemporary.

No, Anaїs’s complaints are not always to be taken at face value and not always in line with reality. This leads to one of the major complaints about Anaїs: her frequent inability to work with reality and tell the truth. To the astonishment of many around her, even when it seemed in her best interest and to her advantage to tell the truth, she frequently seemed incapable of not inventing a rich web of lies.

It was Henry Miller who seems to have first guessed the truth: that this was a core part of her creativity, her need to invent herself over and over again, to fuel her spirit with the risk and adventure of life. It was Miller, who also was evidently particularly non-plussed about either Nin’s lying, her sexuality, or her writing, who saw and told others that Nin was simply living the way many men lived in the world around her. They lied as well, slept with whomever they liked, lied to their other lovers. They, too, lived in their own webs of lies, and no one gave it a second thought. Nin did the same and openly without apology.

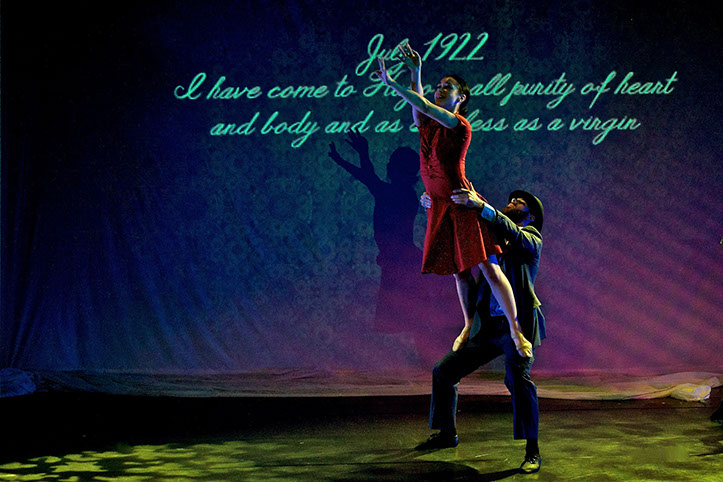

Photo Credit: Barry Weiss

It is this “without apology” that gives a clue to Nin’s real historical significance and is one of her great gifts to feminism. It is the lack of apology that gives the Feminist tradition one of its most powerful weapons at its disposal when confronting the traditional prejudice and inherited restraints facing women down at every turn. To be yourself without apology, that was the silver bullet into the heart of male hegemony.

No, it is not Anaїs’s complaints that we should listen to. What the future and the present listen to and hear are Nin’s unique sense of self. And to this end, there are three very good reasons to pay tribute to Nin today, and why she will be read far into the future.

First, is this sense of self without apology. Nin, though she is long not the first to think or act on this, is one of the first to write about it and make it the core of her art, thought, and life. It is her emphasis on this unapologetically being who she was, damn anyone’s morality or ideas or constraints that makes her a potent precursor to post-War Feminism and one of the reasons she saw a revival of interest in her writing and life thanks to the generation of Feminists that emerged in the sixties and early seventies. Her fame surged again and efforts were initiated to get her full, complete manuscript of her memoirs published. It took awhile. Nin did not live to see the day. But now we have all of Nin’s writing in print and she deserves to be read again.

The second reason Nin will continue to be read and famous is that she may very well be the first celebrity who was a celebrity for celebrity’s sake, for being who she was, as she was, for its own sake, the first “reality star”. Nin was famous for being Anaїs Nin, not the great writer, or artist, or musician, or whatever. She is the first reality star conscious of the fact in a very contemporary 21st century sort of way, far ahead of her time. It was this that puzzled so many of the famous writers and musicians and artists of her time. She had created so little, in terms of what today some would call “product’. Yet she was so famous. She knew everyone of importance and they knew and loved her. She did what she wanted, AND made sure everyone knew about it. There is little doubt that she would be famous if she lived today, that she would have been perfectly capable of thriving in the early 21st century. Maybe she already is.

Photo Credit: Barry Weiss

It is this fact, if no other, that Nin deserves a resurgence in our own time. There is an uncanny way she is fit for our time, even more so than for her own. It may be this aspect that also explains why so many of today’s readers feel a certain affinity for Nin. Why 21st century Feminists find her so readable and interesting. Her writing, now no longer compared to that of Miller’s or any other pre-war writer, now stands on its own and has a certain post-modern lack of hubris in it, a certain provisionality, a clearly casual air about it.

We now read Nin’s writing with different filters than those of her own time; filters that are uncannily more appropriate to it. Filters that are far less likely to misunderstand her, or judge her inappropriately. We now see the mistakes of her biographers and acquaintances: their judgements and condemnations now appear ridiculous, unfair, partially, if not wholly, misguided.

The third reason for Nin’s staying power is similar to why we still read writers like Casanova and will still do so centuries from now, should the human race survive. Not because of his style or exploits, but because he wrote about, in detail, every class and strata and aspect of the century he lived in and about things not mentioned explicitly by anyone else of his time. So he is a unique record of his times and we know things about his era that we would not know otherwise.

Similarly Nin writes about two unique times of the twentieth century - 1920s and 30s Paris, and 40s New York City, the New York that created the post-war New York that everyone eventually DID write about-- and does so like almost no one else.

Both writers share another rare quality: their ability to, in a short pithy sentence or two, describe the essence of another human being, to cut below the surface and reveal things that others are unable to put into words, but once written, become an almost emblematic condensation of what that person is like. Further, they both knew almost everyone who was anybody in their respective worlds, so we get this revealing record of what those people were really like. Ironically, here Nin, the woman who found it almost impossible to tell the truth in day to day life, reveals the deeper personal truth of the most famous people of her age and with it, certain truths underlying her times. For this reason alone, Nin will be read far into the future, because that future, if we survive, will want to know about those times Nin writes about.

This Nin, the writer and reality star of pre-War paris, then 1940s New York, this complex woman who sought to live as men did, without apology, without excuses; this complex, multi-faceted woman, with both dark and light sides, is the Nin of Anaїs. It is the honest portrayal and tribute to all the sides of this Nin that makes Anaїs so worth seeing. There are going to be a lot of people, young women, older women, who are going to discover, or re-discover, Anaїs Nin through this piece.

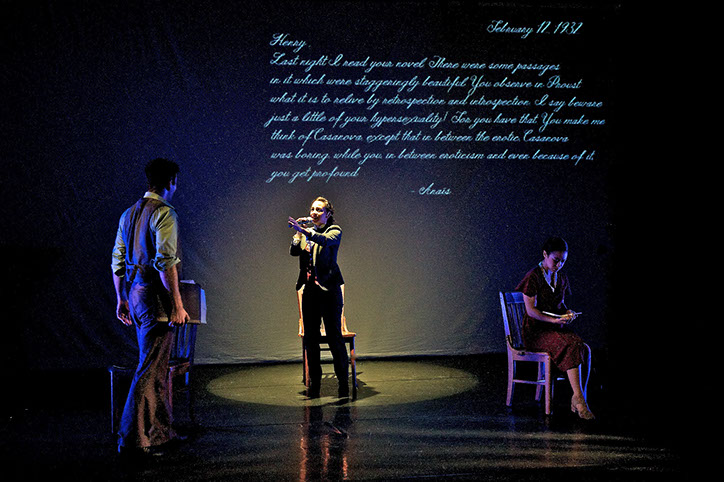

Photo Credit: Barry Weiss

The weakness in Anaїs, and one of the greatest frustrations in watching this show, is that it has not learned more from the rich multi-media tradition preceding it, from Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach to the mature work of Laurie Anderson. Better integration of scrim imagery, choreography, and costume with a better understanding of how to focus the audience’s attention would have helped immensely.

Something multi-media--and opera and modern dance as well--learned long ago is the power of keeping the sound going through the entire piece, no breaks, keeping the audience immersed in the media melange coming at it. Breaking the sound up into discrete songs, as in Anaїs, runs into the danger of slipping into a “review” structure of song, applause, scene change, song, applause, etc. This kills the piece on a lot of levels. It becomes way too static. Anaїs is clearly not a review. There is no need to impose such a stodgy structure onto the entire piece.

But that is not the only thing that is too static in Anaїs: The choreography, especially in the early going, is far too constrained by a too literal conception of narrative. In the dream sequence, where the literal sense of things could be dropped, the choreography comes alive, imagery, costume, and sound come together: dancers rang across the entire stage, their movements gain new fluidity and more inventive shape, their costumes work.

Another curiosity was the decision to, with almost the unique exception of some recordings of Anaїs reciting from her own writing-- a rare and real treat--forego the use of spoken voice. So much of the text on the scrim was vital to a full understanding of the piece, but easily missed when a lot of other things were going on. This would have been easily rectified by adhering to an old multi-media maxim: deliver all necessary content in multiple media, multiple times. In this case, spoken, as well as appearing in text. This would have worked into the overall conception of the work.

But these, in a way, are technical details that do not distract from the reasons for going to see Anaїs, from the reasons why it is a good thing that many people will re-discover Anaїs Nin through this piece, from why this piece is an important piece for our time, an important tribute to an important person who needs to be known by our time in our time.

Anaїs conceived and created by Janet Roston and Cindy Shapiro

Directed and choreographed by Janet Roston

Directed and choreographed by Janet Roston

Cindy Shapiro, music and lyrics

Starring Holly Sedillos, voice, Kate Coleman, dancer [Anaїs Nin]

Michael Quiett, Ben Bigler, Mathew D’Amico, Jacqueline Hinton, Denise Woods, dancers

Joe LaRue, Projection Design

Allison Dillard, Costumes, Derek Jones, Lighting, Jack Wall, Sound

Mixed eMotion Theatrix in association with Diana Raab

Comments

No comments made yet. Be the first to submit a comment