BEYOND THE 805

Art, Theatre, and Costume Design

Chagall at LACMA

The exhibition Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art [LACMA] on view until 7 January 2018 is a special kind of exhibition. It deals with Chagall’s involvement with specific dance performances during his mature years when he was at the height of his powers drawing from long-held connections to music, stage, and dance. Due to the difficulty of exhibiting this type of material, it is probably, unfortunately, a once-in-a-lifetime experience and may never be repeated.

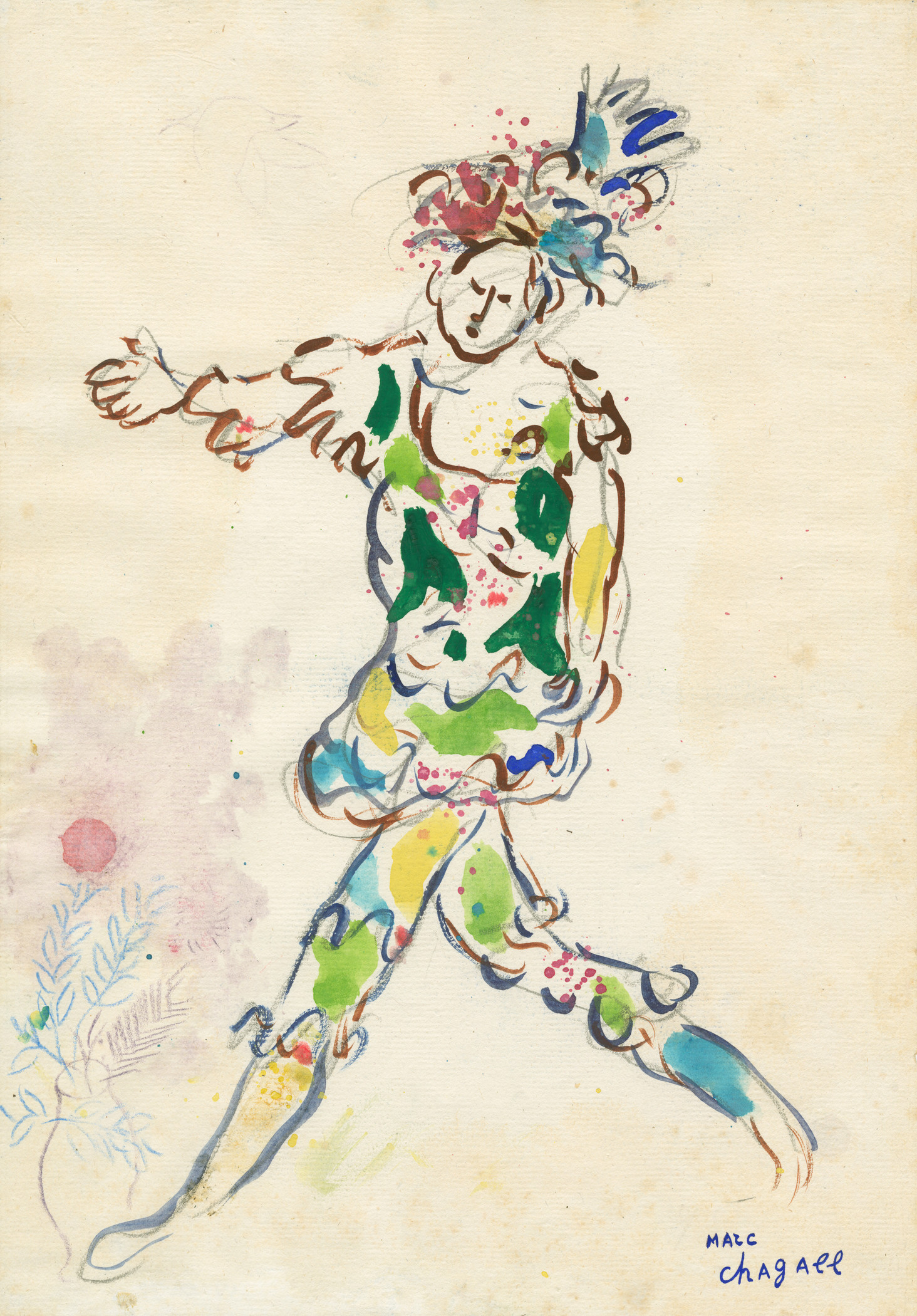

As almost a side note, the exhibition includes most of his best costume and set-design “sketches”, nearly 100, which are for the most part small paintings in water-based media. The earliest ones are fully worked out compositions, essentially full-blown paintings, showing all the best attributes of Chagall’s classic works, except the depth of paint in his primary chosen medium for major works at the time, oil painting. They are beautiful, under-represented works and their exhibition definitely adds to the history of Chagall’s painting development. As his experience with stage and costume design expands, his sketches are reduced to the essentials necessary for preparing costumes and sets and thus approach the look and feel of more conventional design sketches done by any other costume, clothing, or set designer, but with Chagall’s characteristic touch, sense of play and fantasy.

Marc Chagall, Costume Design for Daphnis and Chloe: Young Man, 1958,

gouache, watercolor, graphite, and paper collage on paper,13 3/8 × 9 3/8 in.,

private collection, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS),

New York/ADAGP, Paris, photo © 2017 Archives Marc et Ida Chagall, Paris

The crowning achievement of this exhibition is the costumes, 41 out of hundreds of costumes prepared for the ballets Aleko, Firebird, Daphne and Chloe, and Mozart’s Magic Flute opera, rescued from archives, presented within a theatrical, stage-like exhibition design. Opera director Yuval Sharon and projection designer Jason H. Thompson have gone to great lengths to give us the impossible: the sense and feel of what these costumes might have looked like in their original stage productions. There is also rare, but all too short, film footage of the original live performances giving us a glimpse of how marvelous, truly fantastical, these costumes looked in their original dance performances. After all, some of the greatest dancers of the last century animated these magical beasts and over-size personages designed by Chagall.

Chagall and Theatre

Chagall’s links and interest in the stage appear early and throughout his career. When Chagall, who was originally from Vitebsk, a center in a zone of old Czarist Russia where Jews were allowed to live, albeit not in peace, went to St. Petersburg, a city outlawed to Jews, one of his first and most important contacts was the early Modernist visionary artist Leon Bakst.

Bakst was just back from a triumphal collaboration with Diaghilev’s legendary Ballets Russes in Paris. These were productions which revolutionized how Western European performance and dance productions could be staged. This was in May 1909; Chagall was still a young unknown seeking his direction and future as an artist. In the Russian visual arts scene at that time Bakst was a giant. According to Jackie Wullshlager’s excellent Chagall biography, “Chagall was mesmerized by Bakst.”

In 1906 Bakst was in the process of founding the Zvantseva School and it is clear that Bakst’s Zvantseva costume designs from that time until about 1909 heavily influenced Chagall’s ideas of how to approach costume design. It must be said in all fairness that by the 1940s and beyond, the period covered by the LACMA show, Chagall had taken costume design far beyond anything even remotely conceived at Zvantseva.

One of the things Bakst emphasized was the centrality of color in determining the “world” that a set and the costume design should evoke for a performance. This was one of the key ingredients that could not be determined by the text or music that required the more fully developed vision and deeply understood input of a master visual artist. As this exhibition attests, Chagall took this injunction to heart, for Chagall’s color scheme is central to all his stage conceptions.

Marc Chagall, costume design for The Firebird: Monster with Donkey's Head,

1945, New York City Ballet, New York from Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage

at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through 7 January 2018, copyright 2017

Artists Rights Society [ARS] New York / ADAGP Paris. photo: Copyright 2017 Museum Associates / LACMA.

On top of their color, the wild and wonderful imagination of the costumes in the LACMA show is exhilarating and far different from most anything appearing on our stages today. It is difficult for this exhibition to convey or any of us today to truly experience how eye-shattering these costumes and sets must have appeared to their original live audiences a half century ago.

After an initial sojourn in the west, in Germany and Paris, Chagall returned to Vitebsk during 1914-1915 to join and rescue the famously true love of his life, Bella, his great muse and mother of his beloved daughter, Ida. Things were uncertain as Russia plunged toward chaos and civil war.

The new family lived in Petrograd from 1915 to 1917. Chagall was enlisted to help the nascent Soviet state and began teaching. Throughout this period in Russia many of Chagall’s key contacts were involved in one or the other of the performing arts. Theatre during this period underwent a dynamic and revolutionary development and was a key component of both Jewish intellectual life and the politicized street theatre traditions emerging as part of the Soviet transformation. However, as early as 1919 there were signs that things might become dangerous for a free-thinking, liberal, but relatively non-political painter like Chagall.

Further, Chagall was facing antagonism from the Bolshevik side of things and the arts administration cliques dominated by Malevic and Lissitzky who saw Chagall’s joy of life and open humanism as “old-fashioned, bourgeois, decadent,” though at one time Chagall was Malevic’s boss in the cultural administration. Chagall correctly, but reluctantly, saw that there would be no room for him between these factions and the looming power of those far more reactionary and dangerous factions who would ride Stalin’s coattails into power in the future Soviet Union.

In a public outdoor exhibition for celebrations on 7 November 1918 of the first anniversary of the Bolshevik victory, “astonished Communist leaders asked what Chagall’s animals had to do with Marx and Lenin” [Wullchlager, p. 230]. Party members ridiculed Chagall’s work in the papers. Ironically, Chagall’s work was wildly popular with the common populace, people who had never set foot in a gallery or museum, the true workers the Communists kept talking about. This initiated one of the first waves of Chagall’s popularity beyond the walls of art institutions.

When Kandinsky was ousted by the Constructivists from the Institute for Artistic Culture in Moscow in May 1920, it was correctly perceived as a clear signal that the new Russia may not be a safe place for Modernist painters. The suppression of Jewish theatre and others in Chagall’s circle further reinforced the crushed hope for a better life for Jews in the future Soviet Union.

It is key to notice that throughout all this, for Chagall it was established, indirectly but early on, that the theatre and its livelihood had a central, as well as a psychological, social, and political, role in the sense of freedom and cultural identity that was at the root of his art. Attitudes toward the freedom of theatrical production were a key litmus test for Chagall as liberal ideas and new freedoms succumbed to bureaucratic reaction and eventual suppression.

Trapped in Moscow from 1920 to 1922, the years of consolidation of Red power during the Russian Civil War, [Lenin will be killed in 1924, leaving the pathway open to Stalin to form the hell of the Soviet Gulag and his totalitarian state], the Chagall’s life became increasingly difficult. Allies banded together in their struggles for survival, food, shelter, and some means of artistic expression.

Marc Chagall, costume design for The Firebird: Blue and Yellow Monster from Koschei's Palace Guard, 1945,

New York City Ballet, New York from Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through 7 January 2018,

copyright 2017 Artists Rights Society [ARS] New York / ADAGP Paris. photo: Copyright 2017 Museum Associates / LACMA.

The critic, Viktor Shklovsky observed in April 1920 that theatre and theatrical expression were becoming increasingly active and revolutionary--not only in content but in form, including the creation of a new Jewish Theatre. This activity is commemorated in Chagall’s relatively large [for Chagall at that time] painting, Introduction to the Jewish Theatre, of 1920, and his separate paintings for each of the related arts, Murals for the Jewish Theatre: Music, Dance, Theatre, Literature, also of 1920. A very fine, smaller painting version of the music mural is in the LACMA show.

The truth was somewhat darker than Schklovsky’s enthusiasm. In reality the situation was dire and Chagall and his family were dangerously cut off from the West and any possible source of support for his art. But again, it is noteworthy that the status of the theatre and the life of the performing arts was a key signal for Chagall.

There were pressures to stay and become part of the new vision, the new Russia, but Chagall knew better. In a visit and conversation much later in his life with one of those artists who did stay, Chagall sadly noted that not only had the artist spent his entire career in total obscurity with nothing to show for it, but also, ominously, all his fingernails were missing. A sobering hint of the realities of life later under Stalin.

In a report on the German art scene written in 1920, a young artist, Hilla Rebay, at one time Solomon Guggenheim’s mistress, wrote, “Marc Chagall and Franz Marc, the two painters, are now immortal because they are dead, yet a few years ago they were starving.” [Wullshlager, p. 281] Nothing had been heard of Chagall in Berlin or Paris since 1914 and it was widely presumed that he had perished along with so many others in the Russian civil war. When Chagall reappeared in Berlin in 1922 he was greeted as a hero returned from the dead and his reputation as an artist and leading painter soared from then on between the wars.

As the Nazis approached his newly purchased country home in France Chagall made another harrowing escape from totalitarianism thanks to an invitations from the Museum of Modern Art in New York city. Chagall’s fame and reputation increased still further and new opportunities arose, among which, were new and exciting invitations to collaborate in some of the greatest dance and operatic performances of all time. It is this period that the LACMA show deals with.

Here we see Chagall celebrating the desired freedom for the arts, signalled by new directions in theatre, dance, and music, he had hoped for and envisioned all along. The first collaboration was a commission from the Ballet Theatre of New York [now the American Ballet Theatre] to design scenery and costumes for Aleko, a new ballet based on a poem by the great Russian writer, Alexander Pushkin, “The Gypsies” of 1824. Set to Tchaikovsky’s Trio in A Minor it was choreographed by the legendary dancer, Leonide Massine, who had earlier been one of the greatest stars of Diaghilev’s unrivalled Ballets Russes.

The ballet has a special connection to Los Angeles, as it opened in 1943 at the Hollywood Bowl after a world premier 8 September 1942 in Mexico City and a United States debut at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House in October 1942. This is essentially where the LACMA exhibition starts.

For more information on the specific costume collections exhibited at LACMA and their context within costume design and the original designs for each of the successive productions covered in the LACMA show, see Rhonda P. Hill's article on the exhibition, Chagall -- Fusion of Design: Costume, Performance and Visual Art, at edgexpo.com.

LACMA’s exhibition is adapted from a Montreal Museum of FIne Arts exhibition originally conceived and produced in France in two different exhibitions and generously supported and assisted by the Chagall estate and his descendents. LACMA’s presentation was organized by Stephanie Barron, senior curator of modern art, and the museum’s costume and textiles curators.

______________________

Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage at LACMA exhibition throughl 7 January 2018.

Jackie Wullschlager, Chagall: A Biography, Alfred A Knopf: New York, 2008.

Rhonda P. Hill, CHAGALL – FUSION OF DESIGN: COSTUME, PERFORMANCE AND VISUAL ART, Edgexpo.com.