6 minutes reading time

(1235 words)

Review: Perlmutter’s Directing Hamlet

Review-

First, let us hear it for doing new theatre, new scripts, producing local playwrights’ new plays, or more courageously yet, workshopping new plays. Plays do not bloom, full-grown, out of the head of Zeus. As they say in Silicon Valley, if you are not doing something new, you have no future.

Scholars now tell us that some of Shakespeare’s plays might have been performed over a 100 times before the version we have was written down. August Wilson did a lot of productions in Seattle and Yale and elsewhere before they had their world “premier” in New York. Now those scripts are hailed as the kind that only come along every couple of centuries. Satre secretly workshopped No Exit for long time in Picasso’s Paris studio before unveiling it to a world-war-weary audience in 1944; even then it was later revised. Plays need to be workshopped, performed, revisited, often many times, before they reach their full potential.

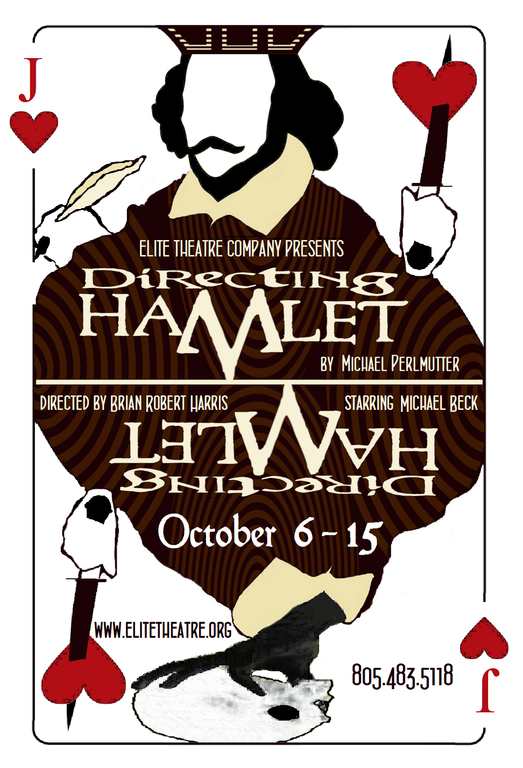

Thus programs allowing the production of new work need to be supported and applauded. In the 805, the Elite Theatre, Santa Paula Theatre’s One Act program, Ventura City College’s One Act Night, and Flying H Productions have all produced new work by local playwrights. The Elite, in particular, lets playwrights self-produce new work or work in progress. It is through this program that Michael Permutter brings us his new play, Directing Hamlet, a well-named new drama.

Set in a rehearsal space, a director and a lead actor rehearse Hamlet. In this production, Perlmutter himself, one of our region’s better actors who has worked on many of the 805’s stages, plays the Director while Michael Wayne Beck, one of our best younger acting talents, who gave us a terrific Packie in Flying H Production’s Small Engine Repair, plays the Actor.

One of the strengths of the play is its use of a minimal set and the pretense of treating the audience as the audience for the rehearsal in the play, including the timing of the seating, thus enforcing a core element from immersive theatre traditions.

Since the play is ostensibly, at first at least, about acting, it sets a fairly high bar for the acting. The script rambles through any number of cliches about acting technique and theatrical manipulation. Perlmutter and Beck deliver their considerable acting chops and the script not only covers all of Hamlet’s major speeches, along with appropriate critique, but contains a good amount of excellent material.

But somehow in its present form, it doesn’t quite work. Or one might say, it doesn’t quite work as well as it should. Why? Don’t get me wrong, in a way it works far better than a lot of other new material that reaches this region’s stages and runs the boards elsewhere. But, as someone once said, “there’s a play in there somewhere” maybe even a darn good one. But a two-person play with minimal set requirements with an imbedded critique of acting, theatre, and modern life, great lines, a set-piece for showing off stellar acting chops with a nifty circularly-referential post-Modernist sensibility? This material could go somewhere.

Maybe it is that the great play in there should probably be at least 40 minutes shorter, and not for the usual reasons. The play is structurally sound [structure is frequently a reason you cut a script]. Part of the problem might be in approach as well as script, for full-tilt passive-aggression, while very effective for building tension in those key dramatic moments is not sustainable in stage life for two hours. OK, it is relieved here by often not always-believably motivated outright aggression, but the key question remains: if you start at full intensity, where are you going to go from there?

For those who might wonder, this play does go somewhere. One of the merits of the script is that it wraps everything up, everything goes somewhere. It gives us clean continuity [not always the case in new scripts]. Maybe even a bit too neatly. One problem is that when the climatic transition comes, it is not quite emotionally believable.

Part of the problem here is, If something happens that in real life would intensify matters, what are you going to do if you are already at max throttle? How does an actor account for the newly elevated intensity of the situation if they are already at full tilt? If someone dies, for example, where are you going to go? If you don’t shift upward in intensity, you run the risk of eroding the play’s emotional integrity, its believability, your sense of the characters involved and their authenticity.

Of course, if you start and stay at the same high pitch, you’ll lose most audiences long before you ever get to such an inflection point or the climax.

And that is what happens; the play loses the audience long before it gets to where it needs to get. Good plays, like music, like really good blues, ebb and flow, drop down, then rise, and repeat. They take you to where you need to go, but they play us along. One of the reasons they are called “plays” to begin with. A play needs to play in order to play us along in order to play well.

The good thing about this script is that it is not really that far away from being a significantly better script. Along with being shorter, it needs to let its emotional baggage drift along in the shadows, forever if need be. It doesn’t have to explain --there’s a lot of explaining in this script. But that is sometimes a good thing, especially when in this script the explanation is misunderstood and we get a critique of explaining itself. Other than that, this play doesn’t have to clarify everything, or anything in words.

What does this play have already? There’s something in there already about Shakespeare, a lot about acting and theatre and manipulation, a bit about life besides what is already said about life by Hamlet, which is a lot, and some good critique. So the play already contains all it needs on the surface, as far as content and lines and situation and character and form go. It probably needs to strip down and ruthlessly edit what it already has, allow itself to play a bit more, to drift without direction. Maybe even listen to Hamlet, after all, taking off from the play’s title: how do you direct that which is already directed towards death?

In Hamlet, Shakespeare lets the play drift off in different directions, even lose itself. It wanders, Hamlet wanders as well as wonders. It questions, but doesn’t jump in with answers very quickly, often never at all, explicitly.

In Hamlet, Shakespeare gives his own advice to actors. Directing Hamlet takes off from that and moves this into the foreground. But in Hamlet, Shakespeare says a lot, both explicitly and implicitly, about theatre, how a play works, how life works, or doesn’t, and in the end, he says something about Hamlet’s real obsession: death. Everything in Hamlet directs itself towards death. In a way, so does everything in Directing Hamlet.

____________________________________

Directing Hamlet by Michael Perlmutter

Directed by Brian Robert Harris

Starring Michael Perlmutter and Michael Beck

Produced by Vivien Latham

Poster by Michael Perlmutter

at the Elite Theatre in Oxnard, California

Directing Hamlet by Michael Perlmutter

Directed by Brian Robert Harris

Starring Michael Perlmutter and Michael Beck

Produced by Vivien Latham

Poster by Michael Perlmutter

at the Elite Theatre in Oxnard, California

Related Posts

Comments

No comments made yet. Be the first to submit a comment